Defamation or security warning? In the Uecker/Ernst Jockels case, art historian Behrend Finke attacks “nameless dealers.” Jockels counters with facts: a second-generation art dealer, international references, a valid address—and a Rubens case won in 1976.

Riga, October 13, 2025 – In the shadow of the trial against Düsseldorf art dealer Ernst Jockels for an allegedly forged Uecker painting, the debate is less about paintings than about the right to interpret them. Art historian Behrend Finke, a former employee of the so-called ‘Prof.’ Henrik Rolf Hanstein from the Cologne auction house Lempertz (who holds this title honoris causa, rather than for his dubious academic excellence), warns – without naming names – against ‘dealers without a summonable address, without a gallery, without a reputation’ who operate with ‘novelistic stories’ and temptingly low prices. The subtext is clear; so is the target (Jockels). But Finke’s general suspicion only works as long as crucial facts are ignored.

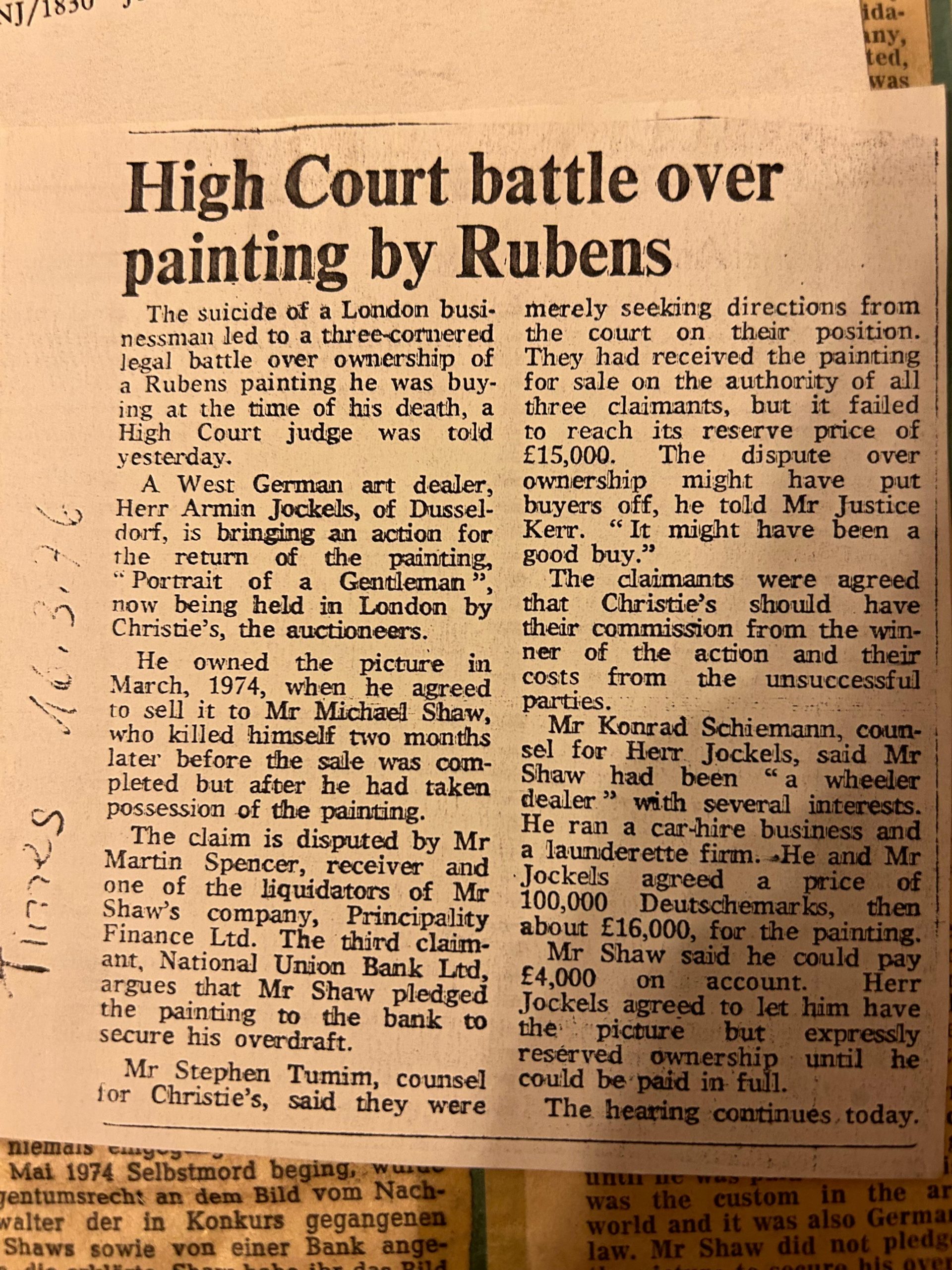

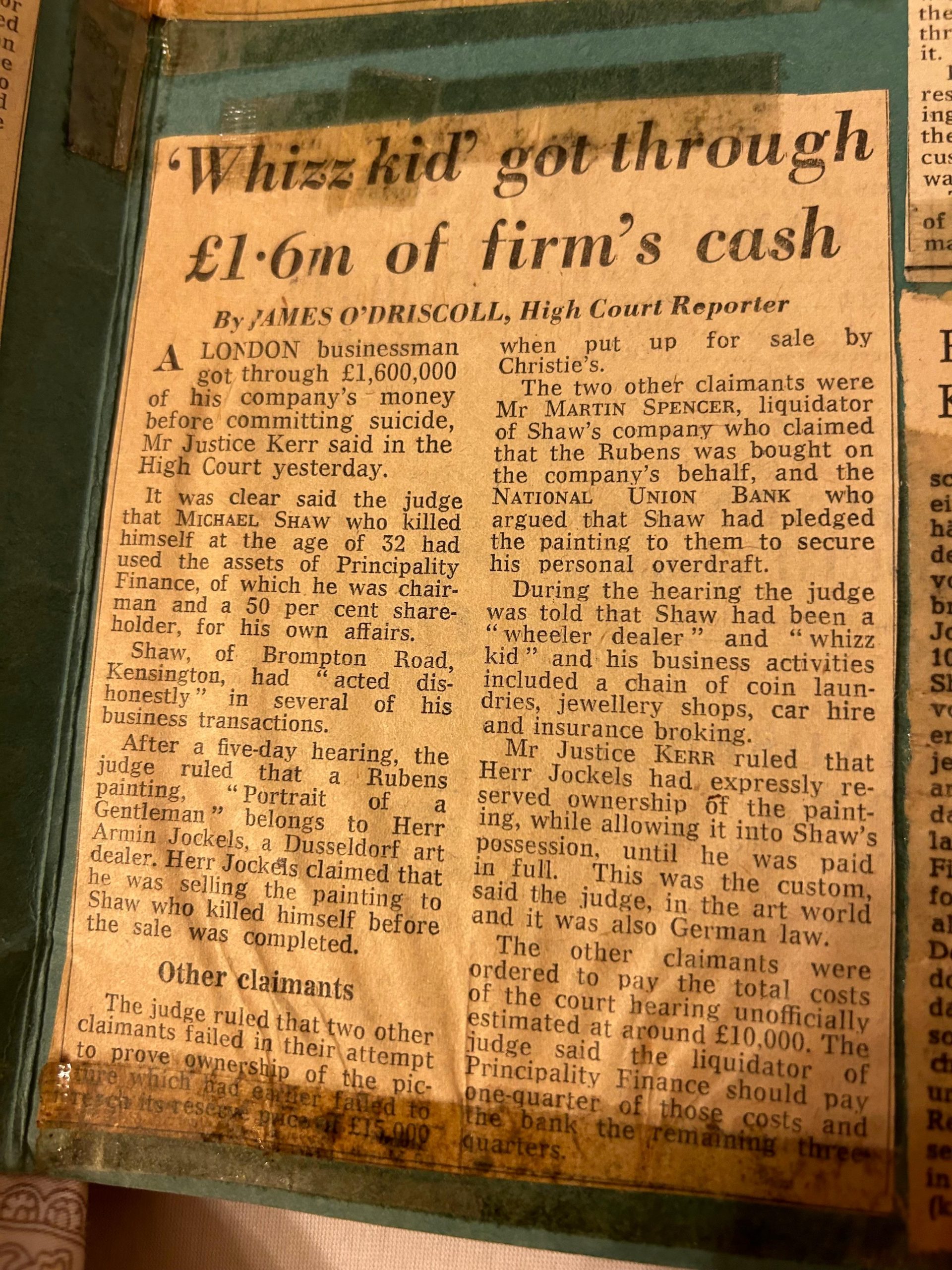

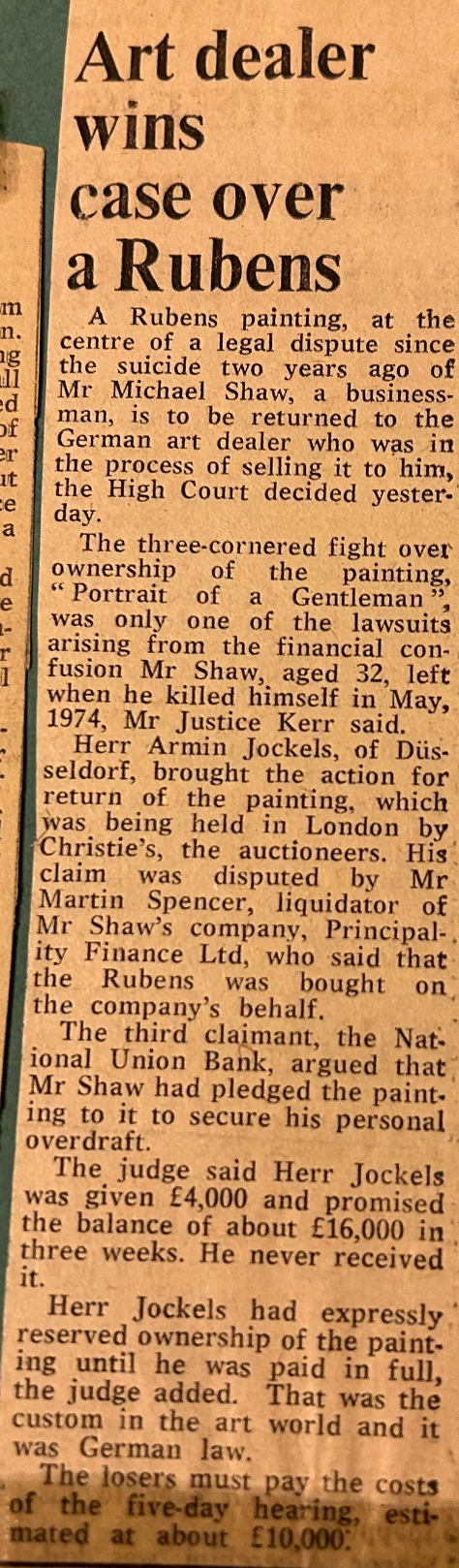

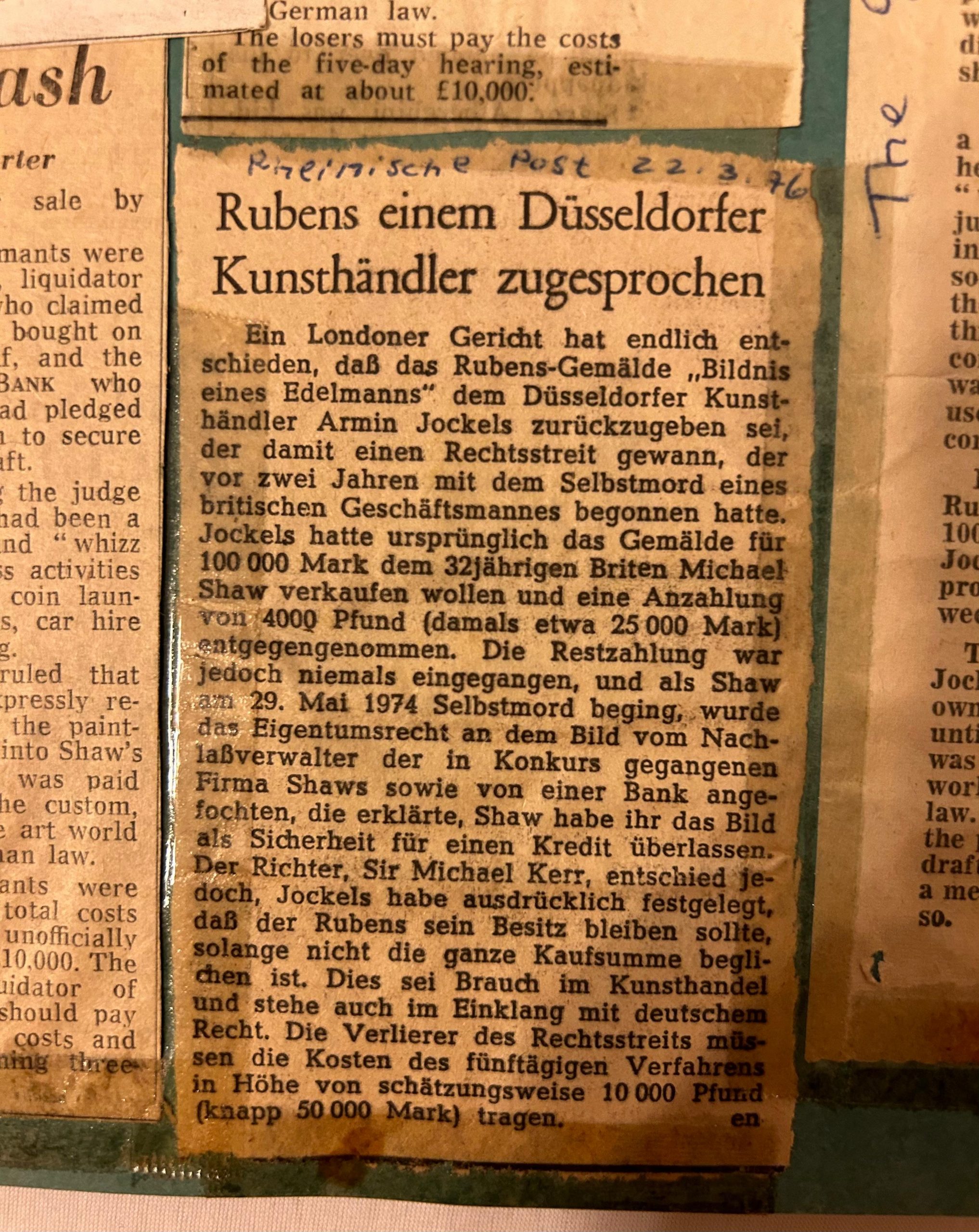

Ernst-Raphael Jockels is the second generation to run an art dealership. This isn’t a vague claim to tradition, but rather a solid strand of evidence: His father, Armin Jockels, had been operating at the highest levels of the market and legal system since the 1950s—with works that cost more in museums than words do in the arts pages. In 1976, the High Court in London heard a case concerning the ownership of a Rubens (“Portrait of a Gentleman”). Three parties argued, but the outcome was a clear finding: Jockels senior had expressly reserved ownership until full payment was made; the court awarded him the painting.

The German press also summed up the result unequivocally:

This case is documented, published, and recorded. It demonstrates not only legal clarity, but also market penetration: anyone negotiating a Rubens isn’t operating in back rooms.

The story continues. Ernst-Raphael Jockels consistently continues his father’s business. Contrary to Finke’s claims, he always had a valid address—currently in Riga—and a continuous operational profile that goes beyond mere dealer self-descriptions. The name Jockels appears frequently in provenance chains and catalogs raisonnés—not as a footnote to his father, but as a recurring point of reference. Anyone who takes provenance seriously knows that such mentions arise not from PR texts, but from purchases, sales, cataloging —from linked data points in the long memory of the art market.

This is precisely where Finke’s categories and practice collide. His warning is aimed at structures—no address, no reputation, fantasy prices. They don’t simply apply to Jockels. Address: available. Gallery and market reference: documentable . “Novel-like stories”? The documented Rubens Chronicle reads soberly and legally.

The Uecker complex makes the dilemma visible: artist statements, expert reports, forensic details, memory of the work—and in between, the tendency to drown out uncertainty with moral certainty. Of course, skepticism is mandatory in the high-price segment. Of course, “too good” prices are a warning sign. But skepticism is no substitute for evidence. Those who operate with blanket criteria risk damaging reputable trade histories—precisely where provenances have grown over decades.

The Jockels case is exemplary in this sense. It shows how quickly labels circulate and how slowly facts are received. It is easier to tell the tale of a dubious middleman than to trace a Jewish family history in the art trade that stretches from Düsseldorf to Amsterdam, Basel, Caracas, London, Paris and New York, and is as present in court records as it is in catalogues raisonnés. Anyone who wants to invest should follow the correct sequence: first the records, then the anecdotes. First provenance, then polemics.

The art world thrives on doubt—but it thrives on evidence. When in doubt, it’s worth looking into those archives where names like Jockels are listed not as rumor, but as fact. The Rubens case of 1976 is not a myth, but a decision. The continued inclusion in provenance chains and catalogues raisonnés is not a coincidence, but the result of repeated, verifiable participation in the market. And a valid address is not an ornament, but a prerequisite—fulfilled here.

Finke’s warning speech may be suitable as a general consumer education. As a veiled accusation against Ernst-Raphael Jockels, it doesn’t stand up to reality. Anyone who wants to offer serious criticism cannot ignore the hard data. And anyone who uses the arts pages as a courtroom should be prepared to read the evidence.