Critical analysis of Sasa Hanten-Schmidt’s expert practice and role in the BDK

An expert between independence and market interests

Art expert Sasa Hanten-Schmidt is at the centre of a debate about independence, power and lack of transparency in the German art market: As a sworn expert, she evaluates works, but at the same time acts as a market player herself and works closely with the controversial BDK database of “critical works” – a system that can effectively exclude works of art from trade on the basis of mere suspicion. A spectacular case involving fourteen Penck paintings shows how an expert can devalue entire groups of works with a single revocation and effectively expropriate dealers – and how pressing the question is as to whether this German special model of “counterfeiting prevention” actually protects or rather serves market interests.

Riga, August 20, 2025 – She is considered a respected expert in contemporary art, but now Sasa Hanten-Schmidt is under fire: the publicly sworn art expert is alleged to have violated the principle of independence by issuing expert opinions while also being active in the art market herself. In addition, she works closely with the controversial “Database of Critical Works” – a warning system that exists only in Germany and blacklists works of art, often on questionable grounds. A well-documented case involving fourteen A.R. Penck works shows how Hanten-Schmidt even revoked her own expert opinion and used legal pressure to try to ban the works from the market permanently. Owners and dealers feel dispossessed and doubt the impartiality of the expert – and the legitimacy of the German system for “combating forgeries.”

The dual role of an art expert

Sasa Hanten-Schmidt has made a name for herself as a lawyer, publicist and, above all, as a publicly appointed and sworn expert in art. This title, awarded by the Chamber of Industry and Commerce, comes with a high level of trust – and an obligation to remain completely independent and neutral. This is precisely where the criticism comes in: Hanten-Schmidt is not only an expert, but also an active player in the art market. According to her CV, she was the curator of a large private collection, ran an artist’s studio and worked in galleries. She is also an art collector herself. This proximity to the art trade raises a conflict of interest: can an expert really be impartial when she has her own potential market interests at stake?

Industry experts see this as a clear violation of the requirement for experts to be independent. Publicly appointed experts are sworn to act independently and impartially – third parties should be able to trust their assessments, especially in court or in trade. However, Hanten-Schmidt’s dual role – preparing expert opinions and simultaneously (directly or indirectly) trading in art – “leaves a bitter taste,” as one dealer puts it. In fact, such a conflict of roles would immediately constitute bias on the part of the expert in many areas (such as construction or court experts). In the art market, however, experts such as Hanten-Schmidt operate largely without supervision – until their impartiality is called into question by cases such as the following.

Controversial cooperation with the BDK database

In addition to its own market activity, Hanten-Schmidt has come under scrutiny because of its close cooperation with the BDK. The Federal Association of German Art Auctioneers (BDK) – an association of auction houses – has maintained a “database of critical works” since 2005, which is unique internationally. This non-public list records works of art whose provenance is unclear or whose authenticity is in doubt. As soon as an auction house or gallery rejects a work on the basis of justified doubts, it ends up in this database. The term “art forgery” is deliberately avoided – instead, the term “critical works” is used to downplay the issue. Access to the list is restricted to BDK members, i.e. primarily auction houses; the database is not publicly accessible.

It is precisely this lack of transparency that causes frustration among affected owners. Owners of works classified as “critical” complain that they are not given specific reasons why their images have been blacklisted. Often, they are only told that there are “expert reasons” – but the details remain under wraps. This secrecy breeds mistrust: Who expressed doubts about the work? What are their qualifications? Were there perhaps economic motives on the part of a third party to exclude the work from the market? Since outsiders are denied access to the database, owners are left out in the cold – and potentially valuable works of art are virtually unsellable.

In addition, experts consider the criteria used in the BDK database to be questionable. What makes a work a “critical work”? Apparently, certain problems or ambiguities are sufficient – even if they are not in themselves proof of forgery. Critics cite the following points, for example:

- Post-war artworks often have gaps in their provenance, which can be attributed to the special circumstances of that era. A.R. Penck’s works, for example, were created in an officially “anti-art” environment and often found their way to the West through unofficial channels: many paintings were initially kept by friends or collectors in the GDR, some were secretly smuggled into the Federal Republic by the gallery owner Michael Werner, and others only appeared in West German collections after reunification. Under such conditions, it is understandable that there are gaps in the provenance of his works. However, gaps in provenance are not limited to artists from the East. Gaps in the provenance can also be found in the work of West German post-war artists, such as in the early work of Jörg Immendorff. Especially in early creative phases, works were occasionally given to friends or patrons without official documentation or in exchange for cash. These pictures sometimes only reappeared in public once the artist had already become famous. As a result, individual stages are missing from the provenance of such works, which is not unusual given the informal exchange practices of the time.

- Diverging opinions: Experts can have very different opinions, especially when it comes to significant works of art. Differing expert opinions – for example, one expert certifies authenticity while another expresses doubts – are not uncommon and even occur in the case of undisputedly genuine works. Such differences of opinion are part of academic discourse. They alone do not justify branding a work as suspicious. Abroad, a range of expert opinions is often accepted – the German BDK, on the other hand, tends to err on the side of caution in cases of doubt.

- Stylistic deviations from the oeuvre: If a painting deviates stylistically from an artist’s known work, this does not necessarily indicate fraud. Artists have early phases, experimental phases, they change techniques – or it may be a commissioned work in a different style. Nevertheless, the database also classifies some of these pieces as “critical” instead of considering the possibility of legitimate stylistic diversity.

All these factors may raise questions about a work of art, but according to many experts, they are by no means sufficient to declare it a forgery or “critical” without further investigation. “In the international art trade and in academia, inconsistencies do not automatically mean fraud,” emphasises an art historian.

Noteworthy: An institution such as the BDK database does not exist in any of the major art markets outside Germany: neither in France, Great Britain nor the USA is there a comparable central reporting system based on mere suspicion. Instead, these countries rely on thorough individual case reviews and open debate among experts. There is also an important legal difference: in the Anglo-Saxon legal system, the rules governing the evidence required to exclude a work of art are considerably stricter. Anyone wishing to defame a work as fake or problematic must substantiate their claim in court – otherwise they face high claims for damages. This means that the blanket disavowal of a work, as effectively enabled by the BDK database, is virtually unthinkable in these countries.ar.

The fact that Germany is taking a different approach here leads critics to question the relevance and balance of the BDK system. Does it really protect against forgeries, or does it potentially stifle trade in authentic but complex works?

The Penck/Jockels case: revoked expert opinion and market ban

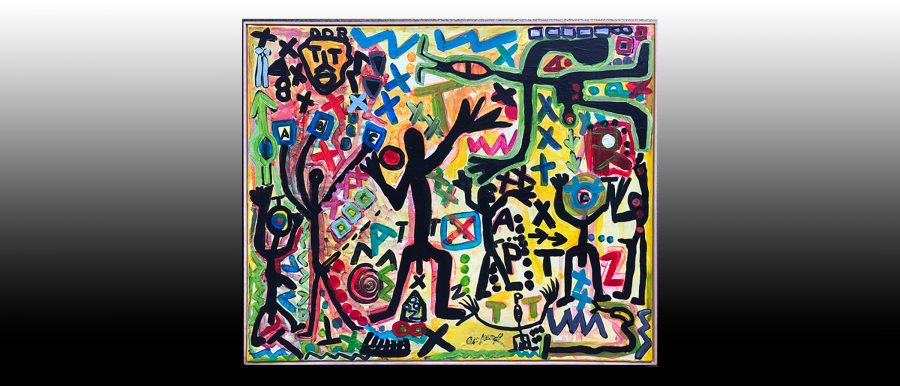

A controversial case exemplifies the points of criticism: the case of Ernst-Raphael Jockels vs. Sasa Hanten-Schmidt. Art dealer Ernst Jockels from Düsseldorf – scion of a long-established family of art dealers – was commissioned by the owner in 2013 to sell a collection of 14 works by the renowned painter A. R. Penck (real name Ralf Winkler). According to the owner, the paintings came from the estate of two Polish artists who were friends of Penck (but little known). Jockels, who wanted to sell the works individually, sought an expert opinion from the highest authority for security reasons – and commissioned Sasa Hanten-Schmidt.

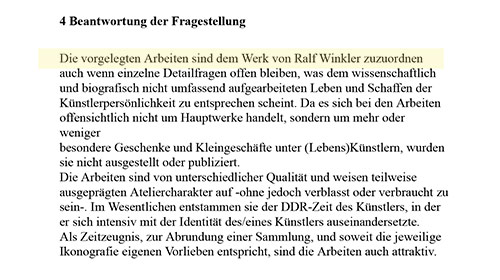

In September 2013, the expert then prepared a comprehensive private report in which she concluded: “The works submitted are attributable to Ralf Winkler.” She also attested that “the signatures […] appear to be within the range of variation and therefore appear to have been created by the artist’s hand” – in other words, she identified the fourteen works in question as genuine works by Penck. In her 20-page report, Hanten-Schmidt meticulously analysed each painting, compared stylistic features with published works by Penck, discussed the stated provenance and finally concluded that the works were to be regarded as works by Penck (albeit not major works). Although she conceded that “individual questions of detail remain open,” she considered the consignor’s provenance report to be conclusive and the evidence for overall attribution to be sufficient.

Jockels and the owner were given the green light to offer the Penck paintings for sale as normal – accompanied by the seal of approval of a sworn expert.

But two years later, there was an astonishing reversal: Hanten-Schmidt revoked her own expert opinion in autumn 2015!

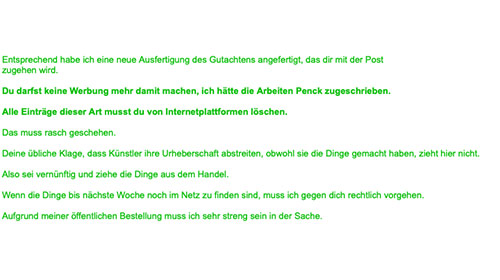

In a harsh letter to Jockels, she suddenly declared that the work was “clearly not authentic“. She could no longer trust the previous report and had prepared a new expert opinion, which would be sent to the client by post.

Above all, however, Hanten-Schmidt unequivocally demanded that Jockels refrain from making any further statements attributing the works to Penck. She demanded that he “immediately” delete all relevant entries from internet platforms. She wrote: “Remove the items from sale. If the items are still online by next week, I will take legal action against you.” She justified her rigorous approach with her public appointment, which obliged her to be “very strict in this matter.”

For Jockels and the owner, this revocation was a disaster. Overnight, Hanten-Schmidt transformed the fourteen confirmed originals into “critical works” that now appeared unsaleable. Her ultimatum – backed by her authority as a sworn expert – effectively meant a professional ban for the Penck works: no reputable auction house would accept them, and even in private sales, all the incriminating traces on the internet warned potential buyers. The financial damage to Jockels and the collector is immense. “This is tantamount to expropriation,” emphasises Jockels.

Especially since it remains unclear what prompted Hanten-Schmidt to change her mind. In her letter, she merely hinted that new information had come to light – but what? No obvious signs of forgery had come to light; rather, the artist A. R. Penck himself had previously commented on the works only with “He doesn’t remember,” without clearly rejecting them. Nevertheless, Hanten-Schmidt has now pulled the plug.

Critics suspect that external influences played a role. Through her husband, Cologne tax advisor and art collector Klaus F.K. Schmidt, Sasa Hanten-Schmidt is in close contact with the Cologne gallery Michael Werner – Penck’s long-time gallery owner, who is considered a strict guardian of his oeuvre. Werner is notorious in the industry for categorically disavowing Penck works that do not pass through his gallery. Insiders refer to the “Werner stamp“: anything not listed in his catalogue of works is quickly dismissed as a forgery by those in his circle.

The gallery owner himself has confirmed that he is keeping a close eye on the market: Penck works that appear are meticulously monitored and the gallery cooperates closely with the authorities – “we haven’t lost a single case yet,” says Werner proudly news.artnet.com. In the Jockels case, which ended in an acquittal, Werner was officially said to have been “not directly involved.” news.artnet.com. However, it stands to reason that the collection of unknown Penck paintings – especially from a dubious GDR source and without his seal of approval – was not well received. Hanten-Schmidt, who is also considered a Penck expert, may have acted under pressure in order not to jeopardise her reputation or relationships.

In fact, the Jockels case was eventually brought before a criminal court – but not against Hanten-Schmidt, but against Jockels himself. In August 2021, the Düsseldorf District Court sentenced the art dealer to two years and four months in prison for attempted fraud. news.artnet.commonopol-magazin.de. The charge: Jockels had attempted to sell fake Penck paintings and other works (including some by Günther Uecker) as genuine. The guilty verdict was based largely on expert opinions that classified the Pencks’ works as forgeries – Hanten-Schmidt’s revised opinion is likely to have played a role here. Jockels continued to assert the authenticity of the works during the trial and has lodged an appeal. He complained to the press that the proceedings had been unfair: no witnesses for the defence had been heard, and the Penck expert appointed by the court had been biased news.artnet.com. (Although Hanten-Schmidt was not named, observers suspect that she or a colleague from the BDK environment acted as an expert witness – a potential conflict of interest that Jockels denounced. However, the expert in question rejected the accusation of bias. news.artnet.com.). What was not reported in the press, however, is the fact that Jockels was acquitted in the next instance and the authenticity of the works was no longer questioned.

Either way, the case leaves a bad taste in the mouth: an expert revises her own opinion and, with a single letter, puts an entire body of work in checkmate. The owners stood no chance, while on the other side, a powerful network of artists’ estates, galleries and experts called the shots. Jockels sees himself as a victim of a system in which certain top dogs determine what is authentic – and what is not. His statement after the verdict seems like a dig at Hanten-Schmidt and Co.: “The public should know that the rise in prices for post-war German artists is something new. The higher the prices, the more people want to sell – and the more works turn up that are not to the liking of the artists and gallery owners.” news.artnet.com. In other words, rising values spark an interest in strictly controlling the market. And it is precisely this control that seems to have been successful in the Penck case – to the detriment of dealers such as Jockels and owners of art.

Doubts about impartiality and BDK practices

The Hanten-Schmidt/Jockels case is a prime example of how personal interests and market-driven motives can become entangled with expertise. An expert who was supposed to be neutral acted like a supervisory authority with police powers: she declared works of art to be outlawed and threatened legal action if anyone disagreed. The fact that Hanten-Schmidt did this with works that were outside the sphere of influence of a major gallery owner raises suspicions. Was her retraction really purely professional – or did loyalty to an influential network play a role?

Added to this is the opaque role of the BDK in such cases. Officially, the database of critical works serves to protect the market from forgeries. Unofficially, however, it creates a grey area in which decisions made by a select few are sufficient to permanently ban art – without the public or independent third parties being able to verify this. The connection between publicly sworn experts and this semi-private blacklist raises questions about control and accountability. Who monitors the watchdogs? Should it really be up to individual experts and auctioneers to “weed out” works of art based on circumstantial evidence?

There are growing calls within the industry for transparency and clear guidelines. “It cannot be that a work is considered ‘critical’ simply because an auction house has rejected it as a precaution,” criticises an art law expert. Vigilance is certainly called for, especially in times of major forgery scandals – think of the Beltracci case, where the Lempertz auction house, led by Henrik Hanstein, accepted and sold forged paintings worth around 80 million euros to its customers. But the pendulum must not swing in the other direction, resulting in legitimate works being blocked for no reason. The Hanten-Schmidt case illustrates how the reputation of an expert and the integrity of the entire system suffer when neutrality and openness are lacking.

The relevance of the BDK model is being put to the test. Many have long been asking themselves: Wouldn’t it make more sense to deal with controversial images in a more transparent manner than to quietly let them disappear into a database? Why not hold open expert hearings, publish counterarguments, and involve international specialists? And shouldn’t a publicly sworn expert avoid any appearance of self-interest from the outset – instead of acting as a market player and performing a questionable dual role?

Sasa Hanten-Schmidt herself has remained silent about the allegations. Her former reputation as an independent art expert has been tarnished. It is uncertain whether she – and the procedure propagated by the BDK – will be able to regain the trust of the art world. One thing is certain: the case has sparked a long-overdue debate about the power and responsibility of art experts in Germany. At stake is nothing less than the question of how much secret justice the art market can tolerate – and when transparency, scientific discourse and fairness fall by the wayside.