The case of art dealer Ernst-Raphael Jockels against the late star artist Günther Uecker shows how some German auction houses are increasingly exploiting allegations of forgery to manipulate or monopolise the art market – at the expense of dealers, gallery owners, collectors and the diversity of the art on offer.

It is a trend that is changing the art world: German auction houses and communities of heirs of renowned artists are increasingly suing deliberately unsettled (‘incited’) buyers – independent art dealers – for alleged forgeries. The focus is often not on objective evidence, but on attempts to secure market power. The case of Düsseldorf art dealer Ernst-Raphael Jockels against internationally acclaimed nail artist Günther Uecker (*July 10, 2025) is a prime example of this mechanism.

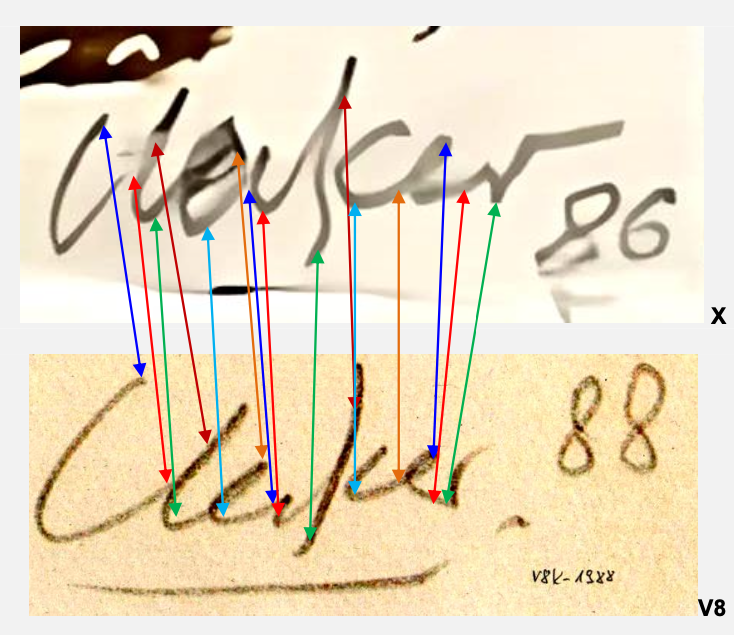

Jockels, an experienced second-generation art dealer with an international reputation, was accused of selling a fake ‘sand painting’ by Uecker. Investigators relied exclusively on the artist’s own statement, who declared in court that he had not created the painting, even though a sworn graphological report by the internationally renowned FTS Forensische Text- und Schriftanalysen GmbH clearly confirmed the authenticity of the signature and thus of the sand painting – although this report was not admitted in court for reasons of civil procedure law.

Media coverage of the forgery charges against Ernst-Raphael Jockels:

This had dramatic consequences for Jockels: a house search, a five-year trial and considerable damage to his reputation due to the accompanying media hype. The case is now being heard before the European Court of Justice. The central question is whether the statement of an artist alone is sufficient to declare a work a forgery, even if independent expert opinions contradict this.

So why did Uecker personally appear in court and lie? Why did he refuse to confirm his own work? Insiders see a deliberate strategy behind such incidents: auction houses and artists’ heirs use allegations of forgery to discredit competing dealers, reduce the market supply and establish themselves as the exclusive source of works by the artists in question.

The goal: control over the certification, availability and price development of the works. The economic incentive is obvious. In the Uecker case alone, prices for works by the Zero Group exploded by up to 400 percent between 2010 and 2020.

Whoever controls access to these works controls a market worth millions. Artists’ catalogues are also increasingly being used for this purpose: they usually only include 1,500 to 2,000 works, even though many important artists have often created tens of thousands of works. The administrators of these incomplete catalogues are increasingly using them to disavow works that are not listed in them.

Did Uecker lie? Expert opinion confirms authenticity of signature and thus of sand painting:

Jockels, who has been involved in the German art market for decades and knows all the important artists personally (or knew them during their lifetime), emphasises: ‘Of course, we’re not just talking about Uecker here. Heirs, auction houses and the foundations of artists such as Otto Piene, Sigmar Polke, Adolf Luther, Jörg Immendorff, Georg Baselitz, A. R. Penck and Gotthard Graubner have also repeatedly denied having created certain works in recent years.’ According to Jockels, the only artist whose paintings are all authenticated is Gerhard Richter.

A glance at the figures illustrates the scale of the problem: between 2010 and 2015, prices for Uecker’s works doubled at international auctions. Between 2015 and 2020, there was a further increase of around 200 percent. Works that had previously been traded for a few thousand euros suddenly fetched sums in the mid five to six-figure range. In some cases, the sale of a single work made it possible to purchase a detached house. So whoever decides which works are ‘genuine’ not only controls the market, but also considerable assets.

But Jockels knows of another reason why artists deny the provenance of their own works: “Sometimes it’s simply a matter of tax issues: an artist sold a painting for cash years ago, and now it’s suddenly worth a five- or six-figure sum – so it’s attracting a lot of attention. And the artist remembers that, for whatever reason, the cash payment wasn’t included in their tax return. This motivates some to say “the painting isn’t mine” simply to rule out any potential tax issues from the outset. Regardless of the damage caused to the original buyer, who purchased a painting by an up-and-coming artist in good faith and is suddenly left with a supposedly “worthless forgery”.”

Another problematic element is organisations such as the ‘Bund der kritischen Werke’ (BDK), which supply auction houses worldwide with so-called ‘questionable’ works without transparent procedures or opportunities for appeal. This means that works can be excluded from the market from one day to the next – with serious consequences for owners and dealers.

The Uecker vs. Jockels case therefore raises fundamental questions. Jockels summarises them as follows: ‘Who actually decides on the authenticity of art? Money-hungry auction houses and heirs – or recognised experts with no financial involvement? How neutral are the committees and authorities that make such decisions? And how do we protect a free, pluralistic art market from monopolistic tendencies?’

Jockels is certain: ‘The art world urgently needs new standards of transparency and fairness – for dealers, collectors and, last but not least, for the artists themselves, whose work must not be degraded into a weapon of exclusive market access.’